About 10 years ago, I watched a Computerphile video, where a young mathematician was explaining how any sufficiently intelligent machine (for example, a stamp-collecting one that could interact freely with the world) would likely wipe humanity off the face of the planet. The video ended with the mathematician stating:

« There comes a point when the stamp-collecting machine becomes extremely dangerous. And that point is: as soon as you switch it on. »

The reasoning was convincing1, and the admonition compelling, so I took it seriously. But it also felt very much “theoretical” given that the state of the art in AI back then was Microsoft’s Clippy2, which was unable to correctly indent a bullet list, let alone annihilate humanity.

Since then, though, the likes of ChatGPT have come of age, and no day goes by without a Silicon Valley billionaire announcing that Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) is a few years away3, proof that the future of AI is now squarely a matter of public debate.

Since I believe in democracy, and democracy only works if people participate, I consider it a civic duty for every citizen to form their own opinion on the following three questions:

Does the development of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and eventually Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) present existential risks to humanity? And if so, which ones?

What should we do, as a society, to mitigate those risks (if we think they are real)?

How can we - as individual citizens - contribute to that societal outcome?

In this post, I investigate whether AGI/ASI constitute genuine existential risks, summarise the leading experts’ arguments and disagreements, and offer clear, practical steps citizens can take depending on what they conclude.

Later I’ll share my answers and a few personal reflections. I don’t expect everyone to agree; think of this as one informed perspective to add to your own reading. If you spot something I missed, I’d welcome a message or a comment. My main goal is to spark your curiosity and help you start your own civic inquiry.

Terminology#

Since I want this post to be useful to as many people as possible, let me introduce a few terms that I will use throughout the piece. If you already have some familiarity with how AI works, feel free to skip to the next section.

- Existential Risk - An existential risk is a threat that could cause human extinction or permanently cripple civilisation’s potential. It is important to keep in mind that these risks are characterised by their irreversibility and global scale. So not all risks related to AI are existential, and this article focuses on existential risks exclusively.

- AI - Obviously it stands for Artificial Intelligence. For this post, it is important to understand that AI is a superset of chatbots like Le Chat, ChatGPT or Gemini. In other words: all chatbots are AI, but not all AIs are chatbots.

- LLM - Large Language Model. This is a type of AI that is designed to process, generate, and understand human-like text. LLMs do not possess true understanding, consciousness, or reasoning capabilities. They operate by identifying statistical patterns in text and lack grounding in real-world experience or embodied cognition. LLMs are the “engine” of conversational AI assistants (chatbots).

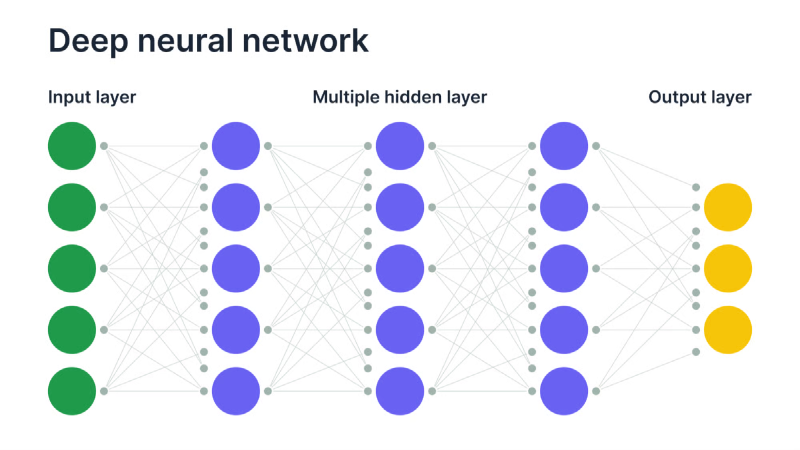

- DNN - Deep Neural Network. This is the underlying architecture of LLMs, the thing that is relevant to know for this post is that DNNs - as the name implies - are inspired by biological brains, which are made up of an intricate network of interconnected neurons that trigger one another.

- Alignment - Alignment refers to ensuring an AI system behaves in ways that match human intentions, values, and goals. It means designing the AI so that its actions are safe, ethical, and beneficial, avoiding unintended or harmful outcomes.

- Narrow Intelligence - Narrow intelligence refers to artificial intelligence systems designed to perform specific tasks or functions within a limited domain. These systems excel in well-defined, constrained environments, such as image recognition, language translation, or game-playing, but lack the ability to generalise beyond their designated scope. Conversational AI assistants are a form of narrow intelligence.

- AGI - Artificial General Intelligence. AGI refers to a hypothetical type of artificial intelligence that possesses the ability to understand, learn, and apply knowledge across a broad range of tasks at a level comparable to human intelligence. The term is useful when used in opposition to the concept of narrow intelligence, but it is - in itself - poorly defined, as there is no agreed-upon definition of human-level intelligence.

- ASI - Artificial Superintelligence. Like AGI, ASI is hypothetical and refers to a form of artificial intelligence that surpasses human intelligence across nearly all cognitively relevant domains. Like AGI, ASI is a fuzzy concept, without a universally agreed definition. Also note that ASI is a subset of AGI (i.e. all ASIs are - by definition - also AGIs).

Don’t Do Your Own Research!#

You have probably heard the exhortation “do your own research” before: besides its use in conspiracy theory circles, the advice is typically given by somebody seeking to understand what is true and fearful that the public discourse may be biased or not representing the full spectrum of ideas.

However, proper scientific research is hard, and this is the very reason why scientific papers are peer-reviewed4 before publication: even people who do research for a living can easily get things wrong, sometimes deliberately5.

So, I counter the “do your own research” with an exhortation of my own: do not replace expert consensus and qualified opinions with armchair certainty. Rather, use your intuition to define what facts and assumptions you want to investigate, and do targeted reading of experts and peer-reviewed sources.

Following my own advice, I did a deep dive of 20+ hours of reading books, watching videos, and listening to interviews6 (coupled with ample note-taking) to answer the two questions above.

In the next section, I will offer a very contrite summary of the points relevant to this investigation. Be advised that I also wrote a companion post to this one, where I offer a longer form version of the summary. Specifically, while in this piece I mostly limited myself to capturing the conclusions the scientists reached, in the companion post I tried to also summarise their reasoning.

ASI x-risk: Leading Voices

The Opinion of Leading Experts#

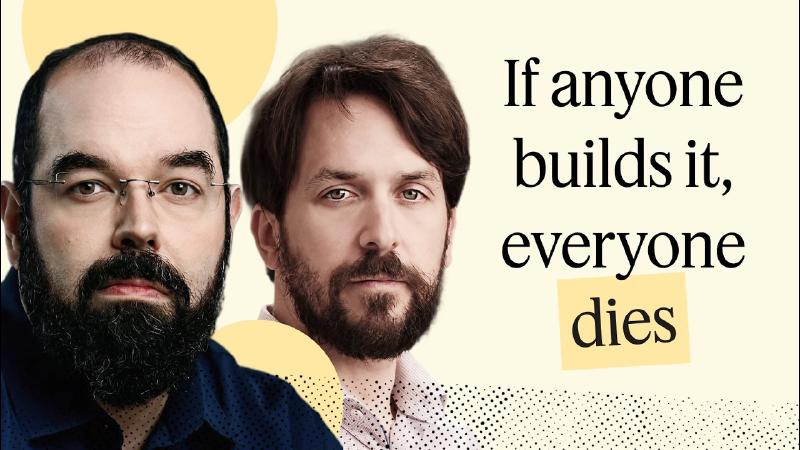

Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares#

I started my journey of discovery by reading “If anybody builds it, everybody dies”, a 2025 book by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI). I chose this book as it sounds almost like the natural sequitur to the Computerphile video. MIRI is a well-respected, long-running institution that was among the first to sound the alarm on the existential risks posed by AI, well before LLMs were a thing and AI was on everybody’s lips.

« If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an artificial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of AI, then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die. »

- What they claim - If anyone builds an ASI using anything like current techniques, the combination of an intelligence explosion with goals that are misaligned with ours will inevitably7 lead to the end of life on Earth.

- Why it matters - Their argument frames the problem as single-shot and uncompromising: safety must work the first time, globally, or the consequences are terminal, which motivates calls for moratoria and precautionary governance.

Ben Goertzel#

However, not everybody agrees on the premises on which Yudkowsky and Soares base their predictions (namely that LLMs will give rise to ASI, and that the values of an ASI would be completely alien to those of human beings). One such person is Ben Goertzel.

This essay and this interview are among the first materials I looked at after finishing the book, as the name of Goertzel is the one that comes up more prominently when I query the internet for counterpoints to Yudkowsky and Soares’ book specifically.

« The core philosophical flaw in Eliezer’s reasoning on these matters is treating intelligence as pure mathematical optimisation, divorced from the experiential, embodied, and social aspects that shape actual minds. […] An intelligence capable of recursive self-improvement and transcending from AGI to ASI would naturally tend toward complexity, nuance, and relational adaptability rather than monomaniacal optimisation. »

- What he claims - Warnings about malevolent ASI overstate the risk; intelligence and values co-evolve, and AGI built through cooperative means and decentralised governance will naturally develop values that will lead it to caring about humans.

- Why it matters - Redirects attention from purely technical fixes to political and infrastructural solutions (decentralisation, open governance) and emphasises shaping incentives and development pathways rather than halting progress.

Ilya Sutskever#

For as much as I loved the hippy energy and easy-going style of Goertzel, I felt that his position was very much a philosophical one. One that I certainly liked but that I also found lacking in engineering specifics (at least in the material I reviewed). Thus, for a more technical take on the problem, I turned to Ilya Sutskever instead.

Sutskever is one of the leading figures in contemporary AI. His work is foundational to modern LLMs and chatbots, and he was one of the founders of OpenAI, which he left after OpenAI cut nearly all funds to AI safety research. He was also one of the people who tried and failed to oust Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, on the grounds that he lied and misrepresented reality to the board and to the investors. Since his departure from OpenAI, he founded his own research company called - case in point - Safe Superintelligence Inc. I listened to this interview.

« I believe it will be easier to build an AI that cares about all sentient life rather than about sentient life specifically, because AI itself will be sentient. »

- What he claims - The existential risk of ASI leading to the extermination of humankind is real but solvable in principle; however, we currently lack the theoretical foundations for safe, general intelligence. In particular, the industry is fixated on the idea of self-improving AI, but AGI may well arise from an ensemble of systems (rather than a single monolith) with limited intelligence but incredibly good at learning.

- Why it matters - Focuses research priorities on developing theories of reliable generalisation and alignment (including capping capabilities and designing value-generalisation mechanisms) rather than only scaling compute/data.

Geoffrey Hinton#

Finally, I turned to the so-called “Godfather of AI” Geoffrey Hinton, who recently left Google specifically to be free to speak out about the AI x-risks.

Hinton was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2024 for “foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks”, and the interview I listened to is this one.

« We have to face the possibility that unless we do something soon, we are near the end. »

- What he claims - Present-day AI misuse (deepfake phishing, bioterrorism, targeted political manipulation, autonomous weapons, mass job displacement…) already poses serious risks, but ASI poses a substantial, hard-to-quantify existential risk and must be prevented from having incentives to eliminate humanity. His approach to mitigation is to regulate capitalism very strictly, as he sees the pursuit of profit as a major cause of misalignment between AI goals and human values.

- Why it matters - Hinton ties technical risk to political economy: profit motives and concentration of power accelerate dangerous deployments; thus, policy and regulation are central components of mitigation alongside technical work.

Yann LeCun#

I also listened to a few shorter interviews with Yann LeCun as he is often cited as at the opposite end of the spectrum, relative to the position held by Yudkowsky and Soares.

That proved to be true: in all the interviews that I sampled, LeCun was confident that “nothing bad will happen” (he is adamant that LLMs will not give rise to AGI). On the other hand, in none of the interviews did he explain in depth his rationale besides pointing out how LLMs and the human brain differ (thus hinting that ASI won’t come from LLMs). This lack of explanation meant that I was unable to compare and contrast his ideas with those of his peers, but he is an influential and often-quoted figure, so it felt wrong not to mention him at least in passing.

Commentary and Synthesis#

All of the materials I went through gave me much to think about8, but my top recommendation would be the book by Yudkowsky and Soares. While their assessment of risk is drastic and hinges on the assumption that LLMs could give rise to ASI (which is a position some of their peers vocally contest), it still makes for an excellent read if you want to understand how to think about LLM’s minds. The second recommendation would be the interview with Dr. Hinton, because - when it comes to spelling out existential risks other than those related to ASI - it is the most comprehensive and clear among the ones I reviewed for this piece9.

Further, I have some observations on how themes unfold across the book and interviews as an aggregate.

On the Problem Side#

- While there isn’t universal consensus on the fact that AI poses existential risks to humanity, a majority of scientists think so10, both in their immediate forms (joblessness, bioterrorism, etc.) and in the more apocalyptic version where an ASI will cause everybody to die. What seems to be variable is how likely different scientists believe various scenarios will unfold because any quantification of the risks hinges on which assumption a researcher makes (path to AGI, speed of capability growth, orthogonality of goals, feasibility of robust alignment, etc.).

- It seems also undisputed that - when it comes to the risk posed by ASI specifically - we only have one shot at preventing it from materialising: by definition an ASI would outsmart us (and succeed) in killing us if it wanted to. Like for the previous point, the assessment of how difficult preventing this from happening may be varies according to the underlying research assumptions.

- Interestingly, most if not all of the AI scientists I sampled for this piece see the concentration of power and capitalism as the structural problems that may trigger the materialisation of those risks.

- There is no consensus on whether LLMs have the potential to produce an ASI or if they are inherently “capped”. It is important to take note - though - that the only practical effect of this disagreement is the time frame for the x-risk linked to ASI: if LLMs have the potential to generate AGI, we are under imminent threat, but if they don’t, we have a bit more time (years or a few decades). However, most of the scientific community is convinced that AGI is coming, one way or another.

On the Solution Side#

- For those scientists who mention them, the solution to present-day risks (those tied to the misuse of AI as currently available) is strong regulation [of capitalise] at a global level.

- For the risks related to the creation of an ASI, everybody seems to agree that the only viable solution is strong alignment11, or in other words: having the ASI never want to get rid of us.

- However, it seems that every scientist has their own thoughts about how to achieve a sufficiently strong alignment: from distributed-transactional systems and co-evolution to a design yet to be discovered, to a laconic “It is not achievable, and therefore we should not develop an ASI altogether.”

On the Debate Itself#

- We lack the proper mental categories for discussing the topic of AI efficiently. Words that make intuitive sense (e.g.: “sentient”, “consciousness”, “intelligence”) in relation to a human prove incredibly difficult to use in the context of AI. And since we are discussing systems that don’t yet exist, with words that have a lot of ambiguity in them, the discussion is hard.

- It is difficult to imagine the right things. This is because of two factors: on the one hand we cannot imagine ourselves not being the most intelligent species on the planet (even if Dr. Hinton has an interesting heuristic for that: « Ask a chicken! »); on the other hand we are also influenced by the collective imagination, so when thinking of ASI, most westerners think of Terminator, while in the east they typically imagine ASIs as being helpful and benevolent, because they are portrayed as such in mainstream media.

My Thoughts#

So, what do I make of all this, at a personal level?

A Dark Cloud…#

All this “not my own research” left me convinced that the AI x-risks are very real but that we - as a society - are absolutely unaware, unprepared, and politically unwilling to mitigate them.

Unluckily, the development of AI is being played out like an arms race, a zero-sum game in which a handful of billionaires are competing to ultimately gain control of society, and the governments appear to be going along with it because they are either clueless, corrupt, or complicit.

Some authors compare the x-risk brought about by ASI to the threat of a global thermonuclear conflict. In the 1950s, that threat led to strong international cooperation to avert it, and they hope the same will happen for AI.

I see the parallels, but I also think there are important differences that may prevent AI from reaching the same outcome. For one, in the case of atomic bombs, humanity had a clear understanding of the consequences: we had just come out of WWII and seen the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Furthermore, it was the Castle Bravo disaster that put that process in motion.

But with ASI we don’t have a shared understanding of the consequences, nor the luxury of a “first smaller incident” to inform our decisions thereafter. The first incident will also be the last possible one.

…And a Silver Lining#

Having a background in Natural Sciences, the position of Goertzel and LeCun that LLMs are inherently incapable of creating AGI (let alone ASI) seems plausible to me.

Beware: mine is nothing more than the intuition of a layperson, but since the premise for LLMs’ effectiveness is biomimicry (i.e. using artificial neural networks to replicate the functionality of the biological brain), it’s worth noticing how our artificial version of the brain is an extremely crude imitation of the real deal. Add to that that our understanding of the actual brain is still - to date - extremely limited, and it is likely that if an AGI were ever to emerge from a synthetic brain, that brain could still be a considerable amount of time away.

This wouldn’t change the severity of the risks, of course, but it would buy us more time. And maybe - with a bit of luck - research on AI will hit a plateau (this has happened multiple times before) and society would have a window of opportunity12. But if that happens, it will be just a [possibly short] window of opportunity, and we will need to swiftly exploit it. With efficacy and effectiveness.

Either way, it appears to me that - while the solution will ultimately be technical - we need a global regulation to limit uncontrolled experimentation and rogue AI deployment.

I think that this will eventually happen. But if I had to infer what will happen based on the past (for example the Covid-19 pandemic), I believe governments will deploy meaningful regulation on AI only after some of the present-day existential risks have materialised. I think this will likely be triggered by mass joblessness (which I consider likely if the LLMs improve further) because governments are typically scared by an angry mob, but also because unemployed people will become an important constituency to cater to.

Conclusion#

Now that the first two questions (What are the risks? What should society do?) have been answered, only the third one remains: how can we contribute at an individual level?

I confess I do not feel as empowered as I would like to be. I lack both the leverage (I am not a politician or an investor) and the expertise (I am not an AI researcher) to make a direct, meaningful contribution to the solution, so all I can do is share my concern. I hope to encourage others to engage with this issue; publishing this post is a small step in that direction.

But if you have either leverage or competence yourself, I think you should seriously consider committing wholeheartedly to the cause of safe AI development. The stakes are so incredibly high that any small contribution towards safety has the potential to change the world.

Regardless of your leverage and competence, these are three possible starting points for your own journey of discovery:

- The centre for AI safety (CAIS) - CAIS is an organisation with the stated purpose of ensuring the safe development and deployment of AI. They conduct research, field building, and advocacy. Their site has an excellent section detailing all major risks related to AI.

- AI safety dot com - This site contains a treasure trove of materials, including courses and conferences and a self-study section with structured paths to understanding the field.

- This video on careers in AI safety - This is a video focusing on technical AI safety, so people with good STEM skills are the primary target. In a poetic twist of events, this is a video featuring the same researcher (Robert Miles) who was in the video I watched 10 years ago.

« There is a quote that goes: “You may not take an interest in politics, but politics will take an interest in you.” The same applies to AI. »

– Ilya Sutskever

APPENDIX#

Additional Reflections on Capitalism#

When I set out on this journey of discovery, I did not expect capitalism to crop up in conversations as often as it did. So much so that it almost felt like a waste not to follow up on those comments with some reflections of my own, but I did not want these political reflections to distract from the main topic, so I collated them here in an appendix.

I am not surprised by the anger and disillusionment of many scientists towards capitalism. The precautionary principle is one of the tenets of responsible science, while Silicon Valley predicates itself on “move fast and break things” (which is a valid product development strategy but also easily used as a cover for the lack of any moral restraints), so there was always going to be friction between these two worldviews.

The closest, most fitting parallel I can draw to what’s happening today with AI is what happened twenty years ago with social media: academia and commentators started to outline the societal costs of social media (misinformation, polarisation, mental health, cyberbullying…) already at the time of MySpace; governments are starting to take [very limited] action only now, after a genocide, dozens of suicides, and who knows how many mental health issues and elections whose outcome has been manipulated.

In fact, I believe that capitalism itself is a fitting metaphor for ASI x-risk. It represents an organising principle much stronger and more powerful than that of any single person or other group of people on the planet (similarly to an ASI), and it seems to be radically misaligned with human values, as proven by the climate collapse, increasing inequality, pollution, environmental damage, and the erosion of democracy coupled with the emergence of the billionaire ruling class.

My guess would be that one of the things a benevolent ASI, loving of all sentient life, would do once they take control of the world, is to dismantle capitalism altogether. This is because capitalism is measurably an unfair system13 that can become rather violent towards all living things.

Historically, the reason why we embraced capitalism is that it represented a better alternative to other economic systems. In other words: it has never been absolutely good, only comparatively good. But in a world where a benevolent ASI would rule uncontested, we would likely enjoy a system of perfect balance, abundance and harmony, and capitalism would be seen as antiquated and immoral, as we perceive today the Roman society of 2,000 years ago.

Since the video is short, and I’ll illustrate its reasoning later in this post, I will not summarise it here. ↩︎

This is a rhetorical exaggeration: in reality, Clippy was retired by Microsoft about 10 years prior, but you got the drift… AI in 2015 was a very far shot from human-like intelligence, with assistants like IBM’s Watson, Apple’s Siri and Amazon Echo often struggling to even understand your commands, let alone execute them. (And if you don’t have a clue about what Clippy is, go to your parents and give them a hug). ↩︎

These people have an abysmal track record of predicting the future, and they are often the perfect illustration of what “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” means. However, they have enough power to be able to set the agenda for the public conversation (often distracting people from what really matters, but this is the topic for another post). ↩︎

Peer-reviewed refers to scholarly work that has been critically evaluated by experts in the same field (who are not the authors) to ensure accuracy, validity, and relevance. ↩︎

Data dredging is the misuse of data analysis to find patterns in data that can be presented as statistically significant, thus dramatically increasing and understating the risk of false positives. ↩︎

I was in bed with a bad flu. When life gives you lemons… ↩︎

I should stress: the authors insist in several places on how certain they are about this outcome. In speaking of the people who prevented a thermonuclear global war (which for them is an equivalent scenario), they state: « They did not see themselves as trying to prevent an improbable, unlikely accident. They worked to un-write a fate already written. » ↩︎

In fact, I changed my mind on several issues in doing this deep dive, and - to be honest - I even recognised some evidence of the Dunning-Kruger effect in my previously held positions. ↩︎

In recommending the interview for its content, I also feel compelled to distance myself from the interviewer, whose demeanour towards the end of the interview I found to be very unprofessional. ↩︎

The most recent survey among researchers was conducted in 2023 and showed a majority of scientists considering AI x-risks real. Furthermore, hundreds of scientists from the most prestigious institutions and private sector research labs signed a declaration that - in its entirety - reads: « Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war. » ↩︎

Strong alignment refers to the goal of ensuring that an AI system’s objectives, behaviours, and decision-making processes are fully and robustly aligned with human intentions, values, and ethical principles across all contexts–including edge cases and unforeseen scenarios. Weak alignment focuses on aligning an AI system’s behaviour with human intentions only within specific, well-defined contexts or tasks. While strong alignment remains to date aspirational, weak alignment is what is an industry best practice already today. ↩︎

A cooling of investments in AI would also mean that the toxic influence of the Altmans, Zuckerbergs and Musks of the world on AI regulation will be felt less than today. ↩︎

The metrics that are most commonly associated with measuring structural unfairness of capitalism are: wealth inequality, income disparity, labour exploitation, access to healthcare and education, housing affordability, environmental externalities, and corporate power and lobbying. ↩︎