Their feedback made clear that integrity - something I consider a basic requirement in leadership - mattered deeply to them. But upon reflection, it also suggested a deeper truth: organisational culture and societal values mirror each other, and moral leadership within organisations is a practical, small‑scale corrective available to ordinary people.

Social Structures are Fractals#

The claim that social structures display a substantial amount of self-similarity across different levels (e.g.: the hierarchy in the corporate world is isomorphic to that in the army, televoting in TV shows follows the same process as political elections, etc.) is well substantiated both at the empirical and theoretical level1.

The claim here is not that social systems are perfectly fractal, but that similar organizing logics (both pro- and anti-social) like democratic decision making or nepotism recur across different scales under comparable constraints (the need for coordination, resource allocation, legitimacy, etc…).

The awareness about this fact is useful both in the analytical phase (explaining the presence of a pattern at a given level by observing how that pattern came to be at a different one), and in the prescriptive one (generalising or specialising conclusions drawn by observing reality at a particular level).

Hence, it is possible to infer many things about how culture in organisations (such as businesses) evolved over time by looking at how the society around them developed.

How the Economy Lost its Integrity#

Many historians and economists2 agree that from the mid 19th century until about 1970, industrialisation has been a force for good3. Among the positive effects on society were the rise of living standards, shorter working hours, longer life expectancy, better access to education, etc.4

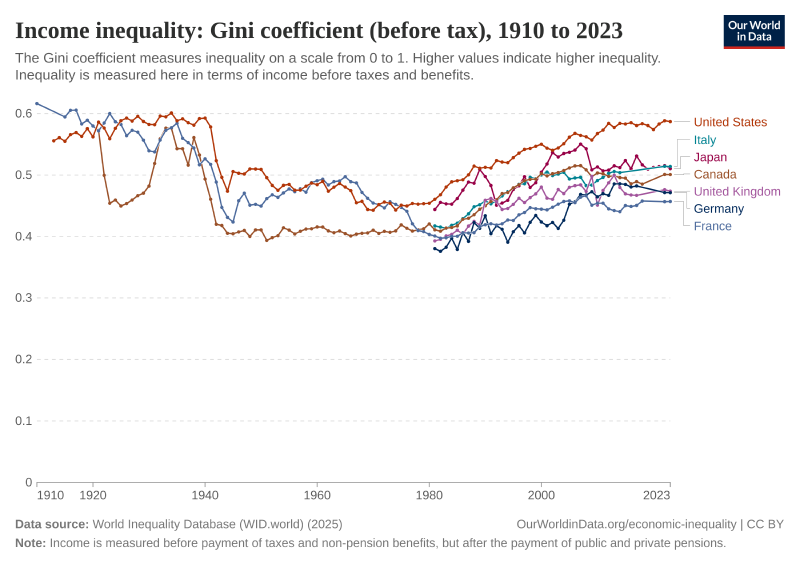

However throughout the 20th century and until now, with capitalism replacing industrialism in developed countries and the advent of globalisation, financial markets and global trade took centre stage. Consequently, as the century progressed, western countries started to de-industrialise5. Eventually, neoliberal policies6 weakened the labour market, access to education and healthcare, social security nets and environmental protection and as a result economic inequality increased7.

In summary: while the period 1850-1970 has seen society at large reaping more and more of the benefits of economic development, the last 50 years have been a steady and accelerating erosion of those gains, with most if not all of the benefits of economic development going to shareholders rather than the people partaking in the economic activity.

How Businesses Followed Suit#

By virtue of the self-similarity of social structures, we know that businesses replicated the larger societal and mental structures of their time. A proper demonstration of this fact would require diving into the management theories that were dominant at various times over the past 200 years - something well beyond the scope of this post - but it is at least possible to exemplify the concept through a gallery of prominent “Captains of Industry” across time (these examples are meant to be emblematic, not exhaustive).

Henry Ford embodied the logic of early 20th-century industrial mass society. His leadership style emphasized standardization, strict control, and efficiency. By introducing high wages for factory workers, Ford aligned production with mass consumption, helping to create a stable industrial working class while reinforcing a hierarchical, mechanistic view of both labour and society.

Adriano Olivetti represented a humanistic alternative during mid-20th-century industrial capitalism. He combined technological innovation with social responsibility, emphasizing community, culture, and worker well-being. His participatory and ethically grounded leadership reflected broader postwar trends toward welfare states, social democracy, and the search for meaning beyond productivity in industrial life.

Jeff Bezos represents entrepreneurial leadership shaped by the rise of platform capitalism. His leadership style focuses on individual performance, opposition to labour organisation8, efficiency, and a hyper-competitive workplace culture, all reflections of neoliberal values like market-driven growth, individual responsibility, deregulation, and competition.

How did we go from a society that built shared prosperity to one defined by systematic exploitation? Once, economic opportunity let people become their better selves, and entrepreneurs raised wages, shortened the work-week, opened schools, and provided medical care. Now we weaken public institutions, strip away social safety nets, and see entrepreneurs build survival bunkers while workers endure conditions so severe they must wear nappies because they aren’t allowed toilet breaks.

There Is No Alternative9#

I posit that the root cause of this shift is that Western economic thinking is unchallenged on the world stage.

At the macro level, the Cold War10 forced the West to prove that capitalism could deliver for workers, in an attempted rebuttal to Marx’s warnings of alienation, inequality, and concentrated wealth. However, the collapse of the USSR not only removed the strategic necessity for a fair society, but it provided the opportunity to also remove the political need to debate it. In particular, the collapse of the Soviet Union was largely presented to public opinion as proof that “capitalism won”11.

So what was once one of the possible economic systems to adopt became economic doctrine, and neoliberalism became pensée unique12 among the ruling class.

In turn, the pensée unique put in motion Gramsci’s cultural hegemony13: businesses and institutions framed the ruling class’s world-view as natural - equating it with freedom and opportunity - until people started to perceive it as self-evident, thus legitimising the existing power structures.

We are back to fractals again. Because cultural hegemony shapes organisational norms, what appears at the macro level (ideology) gets replicated at the micro level (in managerial practice14.

Immoral Leadership#

But what is the mechanism for which managers (who for the most part do not belong to the ruling class and are themselves workers) became wilful agents of cultural hegemony, including crudely exercising coercive powers over their reports?

In other words: how can a manager of a profitable company do things like mass layoffs, paying salaries below living wages, ignoring safety regulations, pressuring reports, doing environmental harm, etc… and still live with themselves?

While the popular view of such managers is to consider them unprincipled profiteers doing immoral things for career advancement and financial gains, moral disengagement theory offers a more insightful explanation for how individuals can engage in behaviours they would normally judge as wrong without experiencing guilt or self-condemnation.

Moral disengagement theory claims that immoral actions get justified through cognitive distortions that re-frame the action as acceptable (“The lay-off is just an unintended consequence of a larger good thing”), deflect personal responsibility (“I’m simply executing orders”), deny consequences (“They will find a new job in no time!”") or blame the victims (“If they were better performers I would have fired somebody else”).

The key observation here is that - while leaders who lack a moral compass do exist, especially at the executive level15 - many more operate in a state of self-serving cognitive dissonance.

The Future is Bleak#

It’s difficult to know with certainty where we are headed, but one observation is that the feedback loop between cultural hegemony and moral disengagement reinforces both: the values and norms we feel are wrong to violate are already few in the hegemonic culture, and as our moral disengagement becomes deeper, it becomes easier to remove them completely from the cultural norm we observe.

While the future is unknown, there is no reason to believe it would substantially deviate from the current trajectory of more inequality, more injustice, more environmental catastrophe. Specifically, one shouldn’t believe in the promise that AI will bring about the end of poverty.

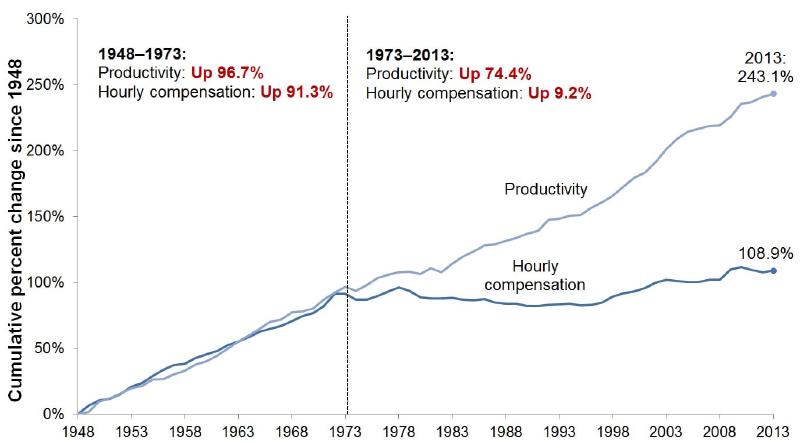

The argument for such thesis is that the increase in productivity will make human work redundant. Similar claims have been made since the invention of the steam engine; and for the past century specifically, the often-referred source for this take has been the economist John Keynes16. However - looking at the historical record - the correlation between productivity and wealth has broken exactly when the business culture we live today became hegemonic.

The lack of positive externalities despite the increase in productivity happened because the social contract around paid labour is not only an economic necessity but also an instrument of mass control through economic structures: poverty is a form of structural violence used to exclude entire portions of society from the political discourse and the democratic process.

It is unlikely (in fact it rarely - if ever - happened in history) that those in a position of privilege would relinquish it even in a situation of abundance for all, as the privilege itself comes from inequality, and it is one of the structural tenets of the current pensée unique.

A further source of pessimism is the ongoing inclusion of AI in our decision-making infrastructure, as this dramatically increases the effectiveness of cultural hegemony.

Like social media feeds, AI chooses what type of information we shall be exposed to and provides credibility and an authoritative tone to even the most outrageous of ideas.

However, while social media are primarily thought and developed as consumer products (defining a clear interface user-content), AI is being embedded deep in our decision-making infrastructure17, and this hides the user-content interface, complicating the situation and making (A) very difficult to understand what role AI had in a decision, even when de decision itself was ultimately taken by a human, and (B) almost impossible to recognise their [deliberate18] bias.

But not everything is lost.

Moral Leadership as an Antidote#

My central claim is that it is this very malaise19 at societal level that drives the wish for moral leadership within businesses, with the hope that it may make our lives better. That’s it: people see moral leadership as the antidote to a bleak future.

My claim rests in part on 200 years of philosophy and social science20 showing that organisations act as the mediation layer between the individual and society at large.

If at macro level the anguish comes from the breaking down of the democratic system, the self-similar antidote at the micro level is a way for workers to participate in the decision-making processes. If at the macro level the dread comes from climate breakdown, the antidote in business is sustainable business practices21. If the macro is racism and xenophobia, the micro is DEI initiatives22, etc….

In business, workers want to be able to influence the social externalities generated by their employers, and where direct participation in decision-making is not possible23, the next best thing is trusting your manager, on the basis that they are moral leaders and will do the right thing.

In fact, I would go as far as claiming that the wish for a moral leader is in and by itself a small scale antidote to the large scale issue of politicians who are corrupted and cowards24.

Conclusion#

I’ll follow up in a future post with a deep dive on what moral leadership is, what mental models can be used to build up our moral identity and courage, and concrete examples to get inspired, but for now my message is this: systems change where people choose differently.

If organisations mirror society, then moral leadership (the everyday decisions to protect people, explain choices, and refuse convenient harm) is a practical lever we can pull now.

It doesn’t require a revolution: if you are a manager pick one concrete step you can take this week (speak up for your direct reports, open a decision to wider input, or make one hiring or pay choice that favours dignity over short‑term efficiency). Watch what it does to culture, and repeat.

Small, consistent acts of moral leadership compound; over time they shift norms, rebuild trust, and make broader political and economic change possible.

Derek Cabrera has published a wealth of work on the subject of systems (including human organizations) self-organizing in recursive structures. A good starting point can be this paper, but for an accessible introduction to systems thinking, I suggest visiting the Systems Thinking Standards Institute (STSI) website and taking their free introduction to Systems Thinking. ↩︎

Among others: Deirdre McCloskey, Robert C. Allen, Gregory Clark… ↩︎

Two disclaimers here: A) there is an obvious caveat to be made about the impact of industrialisation on the environment, B) for simplicity, I am focusing here on the western world, but it is essential to acknowledge that industrialisation also enabled western nations to accelerate their colonialist efforts around the planet. ↩︎

The best consolidated source of peer-reviewed material I could find is this hefty publication by OECD. However, at 273 pages full of methodological explanations and caveats, it is not the most accessible source for a footnote on a blog post, so I also did a few web searches to capture the essence of how things evolved for US, UK, DE, FR. This is what I found: real salary growth of between 150 and 600 percent, length of working weeks falling from 60+ hours to 40, life expectancy going from ~40 to ~70 years, literacy rates from ~50% to nearly 100%. ↩︎

I was unable to find a single source of statistics for this, so I turned to collating a number of different sources (thus the methodology for measuring was probably not identical and the comparison of numbers should be made with caution) to at least illustrate the general trend. Here are the numbers for the period 1970-2020 (reduction in employment in industrial work + reduction of GDP from industrial activity): US (-71%, -32%), UK (-77%, -52%), DE (-33%, -28%), FR (-54%, -37%). ↩︎

To list a few: deregulation, privatisation, tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations, austerity measures, market-based education and healthcare, labour market flexibility, public sector shrinkage. ↩︎

One of the common methodologies to measure inequality is the Gini coefficient, where 0 represents perfect equality (everyone earns the same) and 1 represents maximum inequality (one person has all the income, and everyone else has none). Another source for visualisation of inequality at national level is The World Inequality Database. ↩︎

See here and here for Amazon specifically, and finally here for a more general discussion about corporate union busting in US companies (but also realize that this is not a uniquely US phenomenon). ↩︎

“There Is No Alternative” or “TINA” for short was one of the political slogans of Margaret Thatcher, rooted in neoliberalism and the belief that liberal capitalism and its policies of liberalisation, privatisation, fiscal austerity, etc. are the only viable political and economic system in the world. More details here. ↩︎

Reality is complex and macro-trends like the evolution of economic theories have multiple, interactive forces shaping them. My choice to focus on the Cold War (and the end of it) is justified by its outsized role in shaping the world order in that period, but it shouldn’t be taken as a claim that the Cold War was the only force shaping economic thought in those years. ↩︎

The claim was most famously popularised by Francis Fukuyama in his book “The End of History and the Last Man”, in which he argued that liberal democracy and capitalism were the final and best forms of governance that the world would know. ↩︎

A French expression meaning “Single Thought”, that refers to ideological conformism. ↩︎

Cultural hegemony refers to the dominance of a particular set of cultural norms, values, and beliefs that become accepted as the societal norm. This dominance is maintained not by force, but through consent, where subordinate groups internalise the values of the ruling class, making them see the status quo as natural and inevitable, rather than as a product of power dynamics. ↩︎

A few examples: rank-and-yank, up-or-out, six sigma, bonus incentives, contract-based work, outsourcing, offshoring, zero-hours contracts, stock options, etc… ↩︎

There is a growing body of work arguing that sociopathic traits are common among CEOs and top executives. This is an accessible primer. ↩︎

The essay where Keynes foresees a 15-hour work week by 2030 is titled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren” and was originally published in 1930. ↩︎

For example: financial institutions are using AI to make investment and credit decisions (causing black applicants to be rejected), military forces are using it to decide whom to target (with 10% of the killed people targeted by mistake), universities are using it to grade students (only to discover that the algorithm removed or added points depending on how exclusive their school was), employers are using it to select job candidates (who got discriminated by age), etc…. ↩︎

Some big players in the AI space are quite outspoken about creating AIs that reflect their billionaire owner’s political opinions. ↩︎

I chose to use a bland term here to keep my thesis appealing to a wide group of people, but I have first-hand evidence that for many this malaise has already reached levels that would be better captured with words like “anguish”, “dread” or “alienation”, to name a few. ↩︎

Hegel stated that organisations become “a second family for its members, a mediator between the individual and the state” in 1820, and sociologists and political scientists like Durkheim, Tocqueville, Putnam… have consistently confirmed this in the 200 years since. ↩︎

I’m speaking here of what workers want, not of what businesses are currently doing (which in the case of sustainable business practices is often just greenwashing). ↩︎

Same considerations as above: I’m referring here to the wish for real inclusion, even if - as of 2026 - this is often met by formulaic initiatives and token hires instead. ↩︎

Besides the obvious example of cooperatives, Frederic Laloux has written extensively about more traditional businesses with strong participatory mechanisms in his book Reinventing Organisations. ↩︎

The historian Rutger Bregman - in his 2025 Reith Lectures - proposed a model in which corruption and cowardice would be the leading traits of contemporary right and left political parties. ↩︎