Moral Leadership in Action#

What This Post is About#

In my previous post, I made the case that Moral Leadership (ML) is a powerful force of social change, even when it is expressed within the limited context of a business (or other organizations).

In this post, I will provide:

- A working definition of what ML is (and what is not)

- A heuristic to identify ML

- Easy, actionable ways to start building your ML muscle today

- A critique of my own take on ML

Moral Leadership Matters

An Opinionated Take#

I am unapologetically on team Locke1: I hold that people are naturally inclined to do good, through rationality, cooperation and empathy. And I am convinced that the existence of evil people can be explained by pathologies (Antisocial Personality Disorder, sadism, …), or socialisation (having been born in a context where some form of violence, like racism, misogyny, Islamophobia, … is normalised).

I recognise this is an opinionated take and that other takes may exist2, but the reader who chooses to venture further should know from the start that I wrote this piece for people who share that assumption with me. In other words: this is a post for people who feel a propensity to do good, and want to develop their do-good muscle, and not a post for evil people in search of redemption3.

A Working Definition#

In the most rudimentary terms, Moral Leadership is about using the categories of right and wrong (morality) to make decisions that affect others (leadership).

The Moral Part#

Morality has been debated by philosophers for millennia. Scholars generally agree about the dichotomy between right and wrong, but right and wrong themselves are what Bry Willis4 calls contestable words: a type of weasel words that refer to things that are “not pointable objects nor private experiences, but abstractions that we nevertheless treat as foundational.”5

I claim that any definition of morality is universally incomplete: with a bit of thinking, you will always be able to construct a Gedankenexperiment6 that makes that particular definition problematic. That is to say: you could pick any definition of morality and imagine a scenario in which applying that particular definition to the situation would lead to doing something that you would still perceive as wrong7.

However - and most importantly - I also claim that most definitions of morality are locally sufficient. Meaning that for most everyday situations, most definitions of morality will consistently lead to doing something you would perceive as right, and - crucially - different definitions will lead to the same action.

With an example: you are at the office and a colleague faints. It really doesn’t matter if for you the morality of an action is measured on outcomes (utilitarianism), compliance with moral imperatives (Kantian ethics) or upholding virtues (Aristotelian ethics)… either way, you will know that the right thing to do is checking on them and make sure they are fine.

With a simile: you can use a number of approximations for the shape of our planet: a sphere if you are speaking about astronomy, an ellipsoid if you are using latitude and longitude, a geoid if you are studying orogenesis, etc. But in everyday life, considering your surroundings flat is a good approximation, locally consistent with all of the models.

Bottom line, given this observation on the local convergence of all definitions of morality, my proposed working definition of a moral action bypasses them all and simply is: an action that is performed with the proactive intention to do what is right.

Beside the obvious observation that intent is a necessary condition for ML, not a sufficient one (the heuristics further down in the article will help to assess whether intent turned into responsible action or not), also note that this definition:

- Is a working definition, meaning that is intended to be used for a given purpose and within a particular context (leadership in organisations, which statistically means: middle management in a medium-sized organisation).

- Doesn’t have the ambition of being universal. Rather, it has the ambition to be serviceable in the vast majority of everyday situations. (More on its applicability limits later).

- Is about moral action, not moral outcomes. Not because outcomes are unimportant (that is what the heuristics are for) but because the case in which moral outcomes are already guaranteed by taking a given action is very uninteresting, as it simply becomes the mechanical application of a rule, and not a challenging moral dilemma.

- Puts a premium on moral sincerity. This is because moral sincerity is the threshold for moral agency itself, and it provides the key to distinguish moral engagement from hypocrisy, manipulation or mere compliance.

The Leadership Part#

The second half of the definition has to do with leadership, another contestable word.

We have already tied leadership to the idea of actions affecting others (traditionally, these others are called followers). But I want to push this one step further and state that leadership is relationship. In other words: leadership is not something that the leader has in themselves and casts onto others, rather, leadership exists outside of the leader, and it is cooperatively built by the leader and the followers.

This implies that leadership is contingent to its context. Who your followers are matters. What the shared goals are matters. The norms of the institution you operate in matter… For example: you may want to use internal meetings to develop juniors, but reserve high-risk client presentations for experienced staff.

A working definition of leadership could therefore be: the process of influencing others towards shared goals by adapting one’s behaviour to the context.

Bringing the Two Together#

Once we join the two halves, our final working definition of moral leadership becomes: to pursue shared goals, intend to do right, and adapt your behaviour to the context.

While the definition is not rocket science, note that a corollary to the claim that leadership is contingent to the context is that - while the leader may or may not have certain personal traits or favour certain interaction styles - those are not part of the definition of leadership itself.

Naturally, the same consideration about favourite styles and personal traits not being part of the definition could be made for other professions. However, while in other professions it may be possible to accommodate one’s personal preferences (a lawyer who loves court litigation and one who loves drafting corporate agreements could conceivably build a career by doing only that type of work), in leadership this is rarely possible and always suboptimal.

In fact, in leadership, it is impossible to only adopt a single management style or deploy the same personal trait and at the same time be consistently effective: the followers are not an invariant, and the system leader-followers is in constant transformation. A leader that is a one-trick pony (e.g.: “always charismatic”, or “only using objectives”) is by definition an ineffective leader, lacking the ability to adapt to the context.

Moral leadership - though - is not leadership by an “always moral person” (even if a moral leader is a precondition for it), nor is leadership by “only using morality” (even if a consistent use of morality is one of its outcomes).

I claim that morality is a weakly essential property8 of good leadership and is both expressed in the leader and co-created in the relationship leader-followers. In other words: while it is possible to conceive leadership without morality, and such leadership may even be both legitimate and effective, if such leadership is not grounded in morality, it will always be perceived as defective9.

Practical Heuristics#

Previously, I implied that the working definition of moral leadership that I offer has limits of applicability.

It seems only fair to then complement that definition with a number of heuristics / rules of thumb to verify whether a given leadership decision done with moral intentions falls in the realm of moral leadership, as opposed to simply being self-referential moral justification.

Simpler Rationales#

The more straightforward the rationale for justifying the morality of a decision, the more likely it is ML.

Rationale: In most everyday situations, moral choices require little deliberation: if somebody asked a person to justify why they chose to defend a colleague that was publicly humiliated, their answer would likely be one sentence long: “because it is against HR policies”, “because I believe I must use my privilege to serve others”, “because the humiliation was unwarranted”, etc., and not a 13-page essay about the metaphysical implications of our immanent actions.

Caveats:

- The need for more reasoning places one’s decision further away from that local context where all moral theories are sufficient; that doesn’t mean the decision will be necessarily immoral though, but it will be at the very least more controversial.

- There are decisions - even in everyday life - that are inherently complex to take, so sometimes a more convoluted rationale is just what is needed.

Personal Cost#

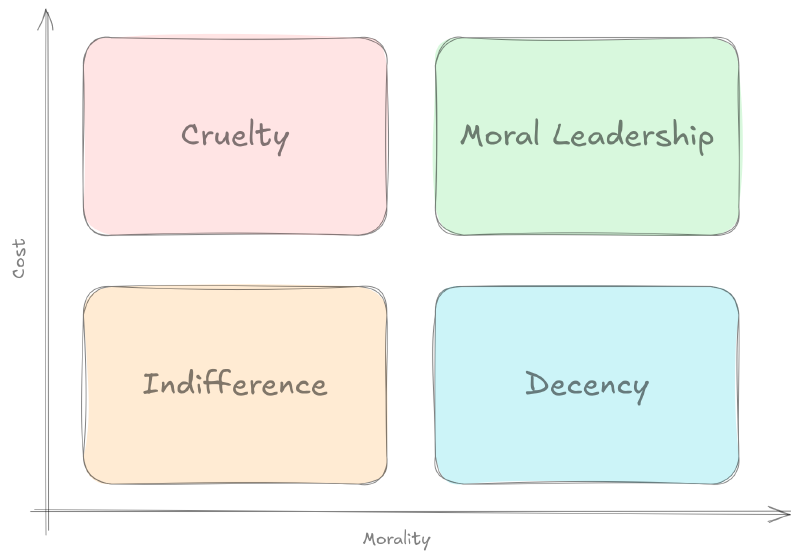

The higher the personal cost, the more likely it is ML.

Rationale: We live in an imperfect world, where cultural and structural violence are the norm. Thus, practicing ML often requires standing out and spending your credibility and status in service of what is right. Sometimes drastic measures like resigning or forfeiting an economic benefit are in order, but in most cases it’s about spending some of your social capital for the benefit of others (like insisting to prioritise a hire to support a team that is overworked, or asking the recruiter to keep looking for candidates with a profile that is more diverse than the one dominant in your industry).

Caveats:

- Beware that a decision against the status quo taken on any principle is more costly than one taken in favour of the status quo and out of convenience, so the correlation with ML is contingent on the principle being the pursuit of what is right.

- Also: not all “cheap” decisions are immoral. Occasionally, the proverbial “low hanging fruits” do exist, as illustrated in the figure below.

Followers’ Consent#

Followers’ consent is a strong indicator of moral leadership.

Rationale: Since the decisions of a leader affect the followers, and followers want to be treated fairly, if the followers as an aggregate disagree with the decision, moral leadership has likely failed.

Caveats:

- Note that the failure mode is dual: it may be that the leader has failed to embrace what is ultimately right, but it can also be that the leader has failed to create support among followers around what - in fact - is the right choice.

- As there are immoral leaders, there are also immoral followers. Occasionally, a follower will resist a moral decision out of self-interest, not moral disagreement (for example, a toxic person who failed to change their ways may resist being removed from the team). When the cost of change is on the followers, lack of consent doesn’t automatically delegitimise the decision.

Value-Based Realism#

Never compromise on principles, but favour progress over moral high ground.

Rationale: Alexander Stubb10 has popularised the concept of “value-based realism”: staying true to fundamental values while engaging realistically and flexibly with a world in which not everyone shares those values, and where real progress requires compromise and cooperation.

That is excellent advice for moral leaders too: leadership is change, so negotiation and compromises are a quintessentially core part of the game. Half a step in the right direction with a bruised ego (for example, bumping up somebody’s salary, but not as much as you wanted, or starting to offer paternity leave, but not as many days as you hoped for) counts infinitely more than being morally pure but making no progress.

Caveats:

- Compromise on the outcome, not the underlying principle is not a guideline but a strict rule. Be especially wary of transactional exchanges: if you are weakening a moral principle in favour of another you are squarely outside of ML. Paraphrasing Benjamin Franklin: “Those who would give up an essential principle, to purchase a little bit of another, deserve neither.”

The Duck Test#

If it looks like ML, swims like ML, and quacks like ML, then it’s probably ML.

Rationale: if we believe that it is human nature to have the tendency to do good through - among others - reasoning, then we imply that somehow, humans are born with an innate capacity to distinguish what is good. The duck test proposed here relies on that capacity: even if occasionally we may not be able to rationalise why an action would be considered moral, we can still recognise it as such.

Caveats:

- As all forms of abductive reasoning, the duck test only yields a plausible conclusion and does not definitively validate it.

- A useful tool to steer clear of confirmation bias is asking somebody else to be the arbiter of your actions. That is to say: while self-reflection is useful, we are all prone to blind spots. If you have access to somebody who you trust to be candid and lucid in their feedback, ask them whether your actions really look, swim and quack like ML.

Cultivate Your Morality#

Here are a few things that I think help with becoming better practitioners of moral leadership.

Name and Describe Your Core Values#

As mentioned at the top of this post, I am “on team Locke” and so I believe that in many instances we can rely on our innate sense of justice to know what is right.

However, I also think that having a set of explicit values11 helps not only with clarity (what is right) but also with self-accountability (having behaviours that are aligned with those values), so my recommendation is to:

- Identify - Write down what you feel are important values for you (aim to have at least 5 of them).

- Sort - Rank them from the most important to the least important.

- Specify - For each of the top values (up to you to decide which ones are important enough to be “core”, but I recommend not to go past 5), write down: A) what they mean (a definition), B) some examples of things that you would do to uphold them, and C) some examples of things you wouldn’t do because they are in violation of those values.

Reflect on Your Motivation#

In a recent video, Daniel Pink has proposed a tiered model of motivation which I believe is a good prompt for reflection. In short, the seven levels he has identified are:

- Avoiding punishment.

- Chasing rewards.

- Seeking approval.

- Pushing for achievement.

- Pursuing growth.

- Anchoring in purpose.

- Operating in freedom.

I would suggest that true moral leadership can only exist in the last two, maybe three levels, which - according to Pink - represents a tiny minority in the general population. I believe this to be the case because the last three are the only ones where the locus of control12 is truly internal and independent from external recognition, and moral leadership is about staying true to oneself, not seeking to live up to the expectations of others.

If you realise you are in one of the first levels, reflect on why that is so, and ask yourself what would it take for your motivation to jump to a different level, and then be the moral leader of yourself, and commit to that change (and yes, sometimes that implies giving up on a big salary at a prestigious company and start looking for a new more meaningful and less paid job elsewhere).

Invest in Your Moral Growth#

Look at your core values and assess how good you are at practicing them. Assess your weaknesses and make a plan on how to improve in those areas. For example, if one of your core values is being honest and transparent with others, but you find it difficult in the moment to give critical feedback to colleagues, commit to prepare that feedback in advance in writing.

The simile here is that of sports. If your ambition is to participate in a marathon, you can’t simply wait until marathon day and hope that you’ll manage. You need to train in order to improve your technique, your conditioning, your resistance to pain.

Deliberate practice#

We only become good by constantly improving, and we only improve through practice. However - for the practice to be effective - it needs to be deliberate. Meaning that your practice needs to be purposeful (with a goal) and reflected upon afterwards.

My observation is that most people rarely take the time to truly reflect and mostly stop at a mere judgement of the outcome (it went well/badly), without digging into the how and why of that outcome, nor braking it in smaller, more specific parts went in either way).

Feedback is a key tool in this. For example, if you are trying to become more supportive of others, you could share this goal with your team and ask for feedback on this specifically during your one-on-ones.

If you practice journalling (and you should!), a good prompt for self reflection could be: “What did I do today that was strongly informed by my core values? Did the outcome reflect my intentions? What did I do well, that could be replicated in other decisions? What things would I do differently? Why? How?”

Find (or Found!) Your Community#

True moral leaders are rare. But there is no reason why that rarity should become loneliness. Make an effort to bond with other leaders who are travelling your same road (in your organisation or outside of it). There is a great power in mutually supporting each other: motivation, growth and opportunities are among the things you could gain from such a group.

Be Courageous#

Above all: be courageous.

Moral leaders have a tendency to sit on the right side of history, but on the wrong side of society. This means that oftentimes doing the right thing requires standing out, often in opposition to the view of those with power over us, which in turn exposes us to real risks. And yet: while risk mitigation13 is part of the equation, applying value-based realism is a must; if you want to be a moral leader, you can’t afford to compromise on principles, only on solutions.

After all, to be afraid of reputational damage or normative exile is human, but to act cowardly is a choice. In fact, it wouldn’t be courage if there were no fear to overcome. To paraphrase JFK: “We choose to be moral leaders, not because it is easy, but because it is hard; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

Failure Modes#

The mental model and tools I offered above are not meant to be airtight. My intent was not to provide a bombproof moral theory for the 21st century, but simply a stepping stone for morally ambitious leaders to become their better selves. I tried to address most of the flaws that I could see in my own reasoning (like good intentions not being the same as good actions, or a blurred boundary between moral evaluation and self-reporting) through the heuristics I proposed above.

In closing, I would also highlight three anti-patterns (failure modes) that leaders who aspire to be moral may sometimes fall into.

The Proceduralist#

This is the aspiring moral leader who doesn’t go past the rigorous application of policies and best practices.

This is not bad, but it is not moral leadership either. For one, the idea that a single set of policies can be equally effective throughout the organisation crumbles under the realisation that context is key to effective leadership. For second, it lacks ambition: most policies on the workplace are designed to meet a minimum standard of decency, not to fundamentally address or resolve moral issues in the organisation. Finally, such a leader typically has an external locus of control, fearing retribution for not following the rules or chasing approval for being thorough.

The People Pleaser#

This is the aspiring moral leader who mistakes approval and popularity as proof of having done the right things.

This is mostly a logical error: while a moral leader is typically appreciated by their followers, depending on the organisational culture, followers can also appreciate leaders who don’t lead and let people do whatever they want, populist leaders who collude with them, or leaders who misrepresent movement for progress.

The Agitator#

This is the aspiring moral leader who mistakes opposition to the established status quo for moral ambition.

This is a similar logical error to the above, another case of post hoc ergo propter hoc. While it is true that often moral change introduces elements of friction and even conflict in the organisation, the conflict is neither desirable nor proof that the change is moral.

As an example, think of somebody who denounces leaders as insensitive and bigoted during an all-hands, branding dissenters as immoral and complicit. The likely organisational response will be for others to withdraw, for the debate to freeze, and for the issue of an inclusive, non-discriminatory workplace to become so charged that very few would feel comfortable to actively engage with it.

This is in fact the most toxic among the failure modes of moral leadership, because it doesn’t only make the leader ineffective, but it poisons the well for the whole organisation, often making certain topics intractable, exactly because people fear that working on the issue will eventually result in getting bogged down in a conflict with said person. On the contrary, moral progress is faster when the moral leader has the capacity to build broad coalitions around change, rather than entrenching themselves on the pedestal of moral purity.

Conclusion#

In summary:

- Moral leadership means to pursue shared goals, intend to do right, and adapt your behaviour to the context.

- Since the road to hell is paved with good intentions, it is important to stay vigilant and edge the risks by deploying a few heuristics to verify we are walking the talk, and by watching out for three specific failure modes.

- Finally, it is important to proactively invest in your growth as a moral leader and above all be courageous about taking action.

If you feel all of the above resonated with you, I invite you to start right now with the first step of self-reflection (name and describe your values). It’s an exercise that typically takes 5-10 minutes, but gives you a momentum that lasts for days.

John Locke (1632-1704) believed people are naturally guided by reason to know right from wrong and are born with basic rights like life and freedom. Authority exist mainly to protect those rights. ↩︎

Locke is often contrasted with his contemporary Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), who thought people are naturally driven by self-interest and fear, and that rules about right and wrong only work when enforced by strong authority. Without such control, society would fall into chaos. ↩︎

By any means: I’d be delighted if a person who is indifferent about harming others would change their mind reading this post, but at no point in this piece will I try to convince the reader they should do good. I’ll simply assume they want to. ↩︎

Bry Willis is an independent scholar; an accessible primer on his work on the language insufficiency hypothesis is here, while his papers are collected and available on Zenodo. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Also known as “thought experiment”, the term was popularised by Ernst Mach, and today the term is used in the scientific community to most commonly denote a thought experiment that would be impossible, impractical or unethical to perform in real life. ↩︎

I’m not breaking new philosophical ground here… Ethical dilemmas are as old as philosophy itself, the most well-known one probably being the trolley problem. ↩︎

Weak essentialism holds that some properties are necessary for a thing to properly be the kind of thing it is. These properties are not definitional (those pertain to ontology) but normatively essential, meaning that they are required for proper realisation, not for bare existence. ↩︎

Authoritarian leaders are a good illustration of this concept. People like Donald Trump or Adolf Hitler got to power via a fair process (legitimacy), had masses of rabid followers (alignment), took decisive and very consequential action (bias for action), and were able to swiftly create long-lasting change (impact). These are all characteristics associated with highly successful leadership, and yet… their lack of morality makes it so that their leadership is seen as inherently defective.

A complementary (and admittedly off-topic) observation is that ineffective leadership can occasionally still be regarded as worthy of emulation when the leader displays a great deal of morality (think of Jimmy Carter or Marcus Aurelius, for example). ↩︎

Stubb is Finland’s president at the time of writing. He illustrated the concept of value-based realism in his essay “The West’s Last Chance” available here. ↩︎

Values are the beliefs or principles that guide what a person considers right, important, or worthwhile. ↩︎

Locus of control (LOC) is a psychological concept denoting the degree in which individuals believe events in their life are either the result of their own actions (internal LOC) or the result external factors (external LOC).

For example: upon having baked a cake that didn’t taste that good, an individual with strong internal LOC would likely say things like “I must have failed to follow the recipe” or “I should modify the recipe to account for XYZ”, while one with a strong external LOC would likely say “The recipe I followed is bad” or “The ingredients that were sold to me were of poor quality”. ↩︎

A couple of examples of things that a moral leader could do to mitigate risks to themselves could be: having a private conversation with their manager before something becomes of public domain (not to ask for permission, but to avoid taking them by surprise, and giving them time to reflect beforehand instead), to find one or more allies who would join forces to take action with them (there is strength in unity), etc. ↩︎